For more than two decades, the International Space Station has been a symbol of presence, a platform defined by continuous operations with enough room to sustain a permanent crew, host complex experiments and test new materials. As the ISS approaches retirement, the conversation about what comes next often focuses on launch vehicles, cost or timelines. But one factor matters more than most others and will ultimately determine whether the next era of space delivers real value: habitable volume.

In the emerging commercial space economy, volume is not an abstract design metric. It is the currency that drives productivity, throughput and market growth. Without sufficient volume, human spaceflight becomes episodic, research becomes constrained and commercial activity stalls. With it, space becomes a place of sustained work, scalable manufacturing and durable economic return.

Why volume matters

Habitable volume determines how many people can live and work in orbit, how long they can stay and what they can accomplish while they are there. More volume means more crew, more experiments running in parallel, more payloads in different stages of development and fewer tradeoffs between safety, operations and science. It enables continuous operations rather than short visits, which is the difference between demonstration and production.

Crew rotations are a clear example. A station with limited volume can only support small crews for short durations, forcing frequent handoffs and operational pauses. Larger volume supports permanent crews, smoother rotations and the institutional knowledge that builds when teams work together over time. That continuity matters for safety, efficiency and the ability to take on complex, long-duration research programs.

Science and manufacturing scale with space

The same principle applies to research throughput. Many of the most valuable microgravity investigations, including drug development, advanced materials and semiconductor research, require controlled environments, dedicated equipment and time. Limited volume forces experiments to be queued rather than run concurrently. Larger volume allows multiple investigations by multiple companies and agencies to proceed simultaneously, increasing output and accelerating discovery.

Manufacturing cycles are even more sensitive to space constraints. Producing materials in microgravity is not a one-off experiment. It is a process that includes setup, growth, monitoring, iteration and return to Earth. Adequate volume enables full lifecycle operations, from staging raw materials to running parallel production lines, storing finished products and preparing the next cycle without stopping work. That continuity is what turns microgravity manufacturing from a curiosity into a business.

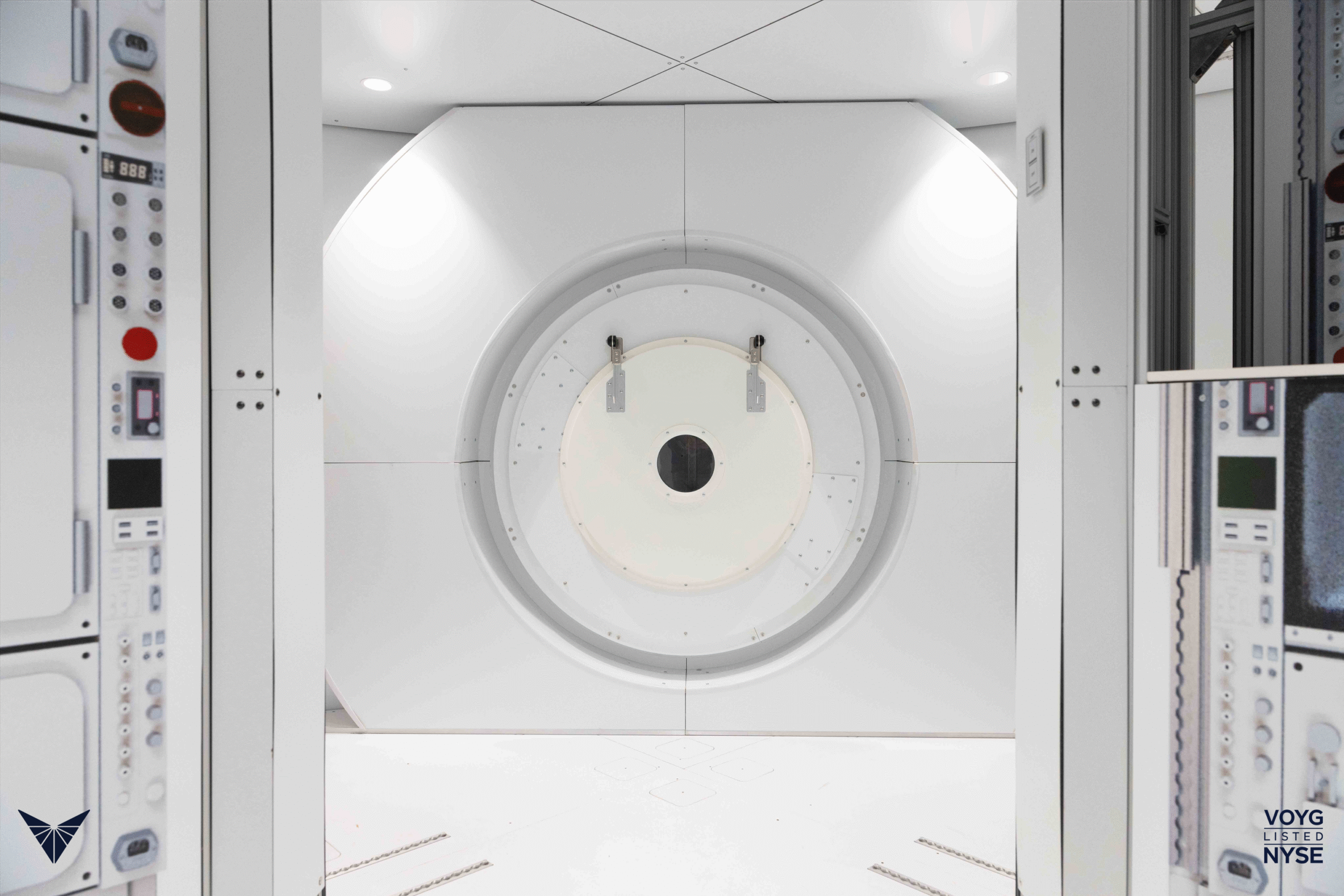

Volume also drives efficiency. Platforms designed with sufficient scale, such as Starlab’s nearly 400 cubic meters of pressurized internal volume comparable to the ISS, can support more activity within a single system and make better use of transportation to and from orbit. Higher demand enables more frequent flights, spreads fixed costs across more users and lowers the cost of station operations and access for everyone, reducing the cost per experiment, per crew hour and per manufacturing cycle. Advanced automation, digital monitoring and AI-enabled operations further increase productivity, allowing crews to focus on high-value work while systems manage routine tasks. Scale and intelligence together are what make sustained operations affordable.

Markets follow capacity

Commercial markets form where access is reliable and capacity is predictable. Companies will not invest in space-based research and manufacturing if they cannot count on uninterrupted operations, sufficient crew support and room to grow. Habitable volume underpins all three.

A platform with meaningful scale lowers barriers to entry for new customers and helps keep the market viable. It allows startups and large enterprises alike to run experiments without displacing others. It supports a mix of users, from scientists and manufacturers to national security missions, without forcing tradeoffs that limit participation. Over time, that diversity of users creates a resilient ecosystem rather than a single-purpose outpost.

This is why replacing the ISS is not about matching a launch date alone. Smaller stations cannot support today’s level of ISS demand, let alone future growth. Reducing available payload capacity and crew time risks pushing companies out of the market entirely and driving international partners to seek alternatives elsewhere. It is about matching or exceeding its operational capability from day one. Any gap in volume becomes a gap in throughput, workforce continuity and commercial confidence. Once that confidence is lost, it can take years to rebuild.

The foundation of a durable space economy

The next chapter of human activity in low Earth orbit will be defined by platforms that can support real work at real scale. Habitable volume enables steady crews, high research throughput, repeatable manufacturing cycles and growing commercial markets. Without it, space remains a series of short missions. With it, space becomes an economy.

As the ISS era comes to a close, the lesson is clear. Allowing a gap in capability would have consequences beyond science and commerce. It would weaken the U.S. industrial base, push research and talent overseas and risk ceding leadership in low Earth orbit to competitors such as China. Presence alone is not enough. Capability matters, and capability begins with volume. Starlab is built to provide the scale required to sustain leadership, accelerate discovery and unlock the full potential of the commercial space economy.